NEPAL’S SEISMOLOGY IN SCHOOLS NETWORK USING RASPBERRY SHAKE

November 29, 2018

HISTORY

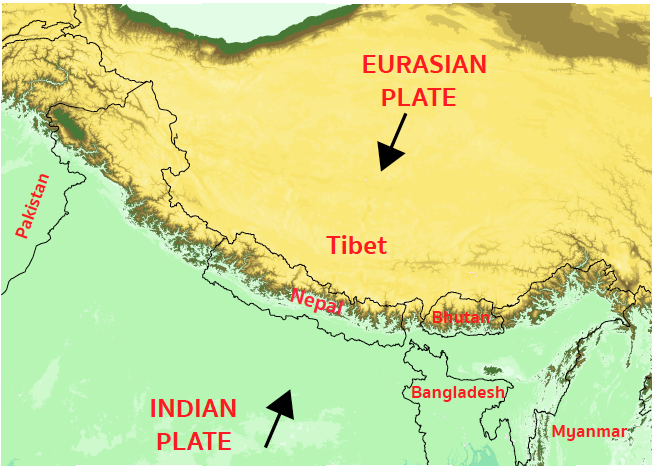

Nepal lies over the convergent plate boundary between the Indian and Eurasian plates. On the surface, the plate collision created the impressive Himalayan mountain range, extending over a distance of 2,500 km. Below ground, this plate collision has another impressive feature: it is the most seismically active zone on any continental plate. The region of Nepal has experienced major devastating earthquakes throughout its human and geological past. In its history we know today, earthquakes have claimed thousands of lives and caused significant damage. The recent 2015 Gorkha earthquake alone killed nearly 9,000 people and injured approximately 22,000 others. It was the most important natural disaster to hit Nepal since the 1934 earthquake, yet casualties and damage were well below those of likely scenarios. Nepal is certainly not out of danger and future catastrophic events remain highly probable, even in the short term. Following the 2015 Gorkha earthquake, Nepali people are hence eager to learn more about earthquakes and how they could improve their own safety.

CURRENT SEISMIC MONITORING

The National Seismological Centre (NSC) in Nepal was established to monitor the seismicity of the country as early as 1978. Currently, the National Network consists of 21 short-period and 7 strong-motion seismic stations. The network has provided over 213,000 earthquake locations since it began operating.

The sensors that are run by NSC are very sensitive and hence expensive, as in all observatory networks. However, beyond research and earthquake monitoring, efforts to improve the population’s preparedness or to reduce earthquake related risks were limited, at least geographically. This is partly due to the remoteness of many areas with respect to the capital Kathmandu. The main problem however, is that earthquakes and related topics are not taught in school, therefore the population mostly lacks reliable information about the process and practical steps to follow.

Raspberry Shake installed in Ekata Secondary School in Baglung district on 2nd May, 2018. This was the first low-cost seismograph installed in Nepal.

It is in this context and for the above reasons we started a regional initiative to improve earthquake education in Western Nepal. Our main tools are Raspberry Shake seismographs: low-cost seismological instruments that we can install in schools across the region. These stations are suitable for detecting and explaining local seismic activity and are exactly what is needed for our educational programs which we implement into classes in local schools. We hope that once our initiative is running successfully, the example will spread, and other schools will start to purchase sensors for their own use. In this way our project plans on expanding through crowdsourcing, as more of the local population get involved, accessing and seeing for themselves the importance of the seismological data collected.

Picture of the school taking part in the pilot program Ekata Secondary School, west of Pokhara, Baglung district. The first pilot station is installed here.

POTENTIAL THREAT

According to historical records, the greatest earthquake reported in Western Nepal occurred in 1505. Since then no large earthquake has been documented in the region, making a clearly identifiable gap in seismic activity of 500 years. Considering the continued accumulation of stress, this points to a high level of seismic hazard. Recent publications in Nature Geoscience and Science conclude the same and state that the energy stored beneath Western Nepal is sufficient to produce a major earthquake at any time. This is the reason that drives us to realize this project in Western Nepal.

INSTALLING THE PILOT RASPBERRY SHAKE STATIONS

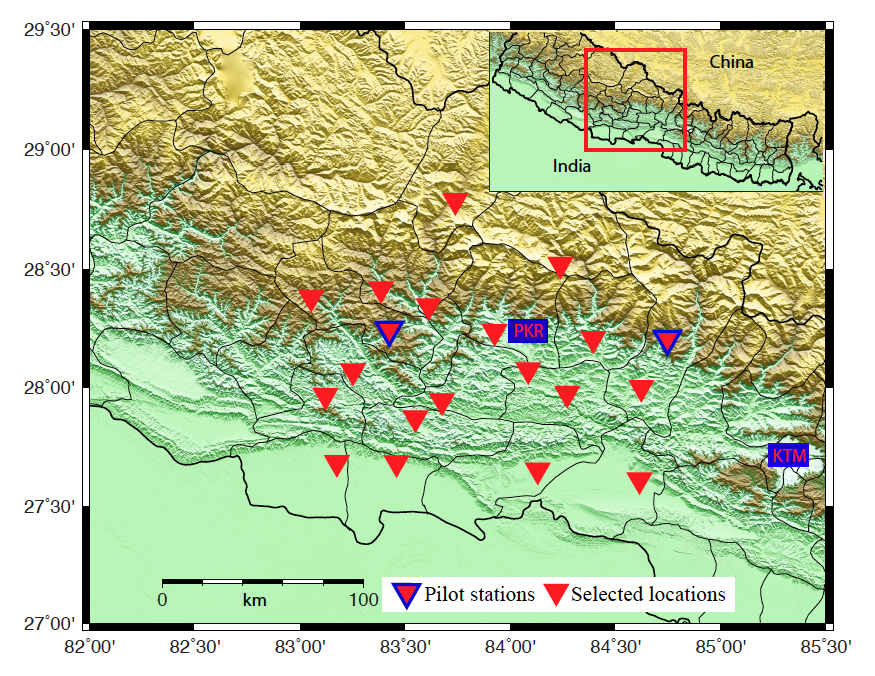

To prepare the way for the installation of the school seismic network, we have travelled across 20 districts of Western Nepal in April and May 2018. Thanks to a high level of interest, we have established official agreements at 20 sites, one in each district (see the selected locations on the map).

Educational seismology network map in Nepal, with already 2 operating Raspberry Shakes.

The schools have agreed to participate in the Seismology-at-School program in Nepal, which now has a legal framework. As the first practical steps of the program we have installed two pilot Raspberry Shake 1D seismograph stations. One in a school in the Baglung district, west of Pokhara city, and another one in a school in Barpak, the village at the epicentre of the 2015 Gorkha earthquake. The Baglung station has been recording since 2nd of May 2018, and streams data in real-time: R023E.

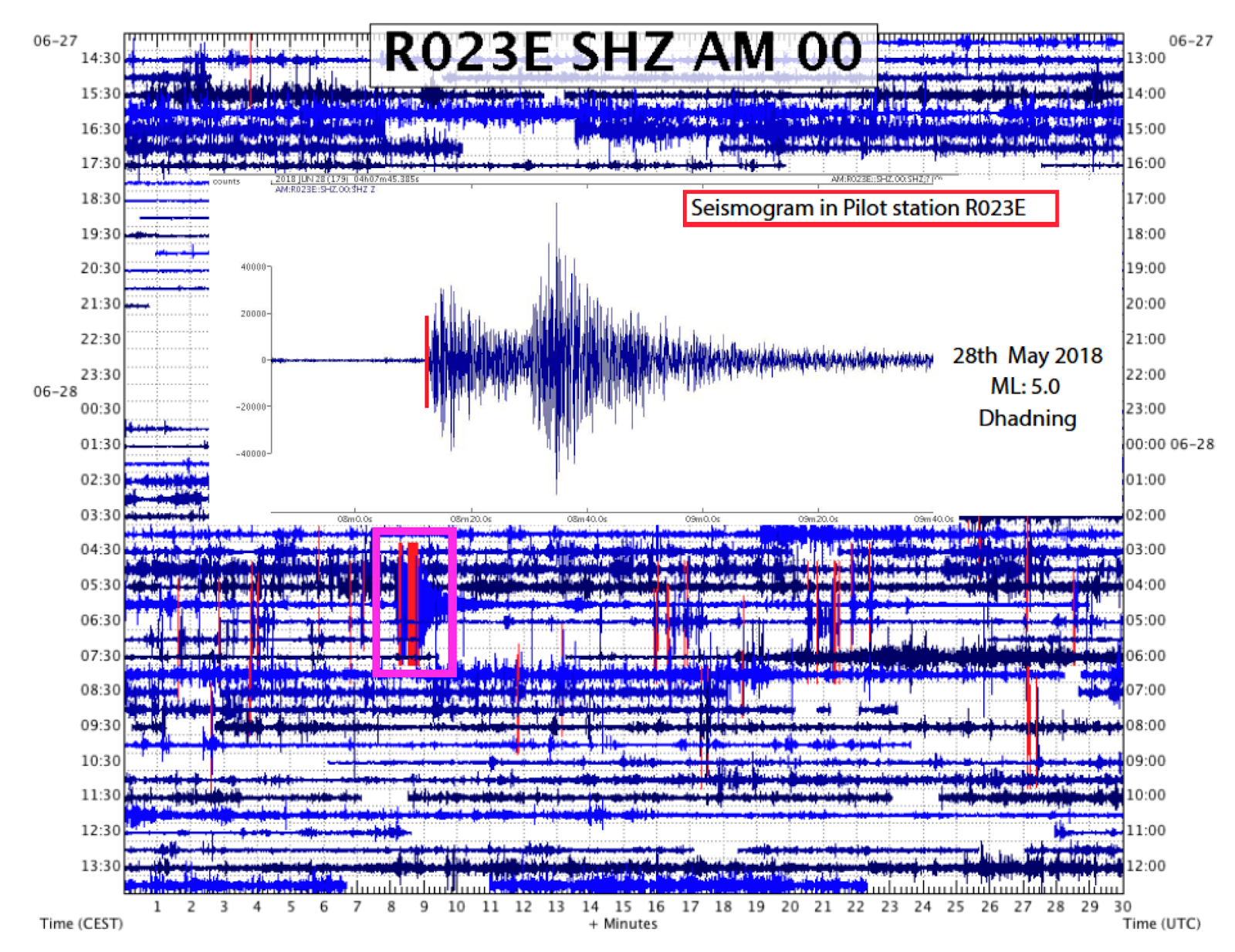

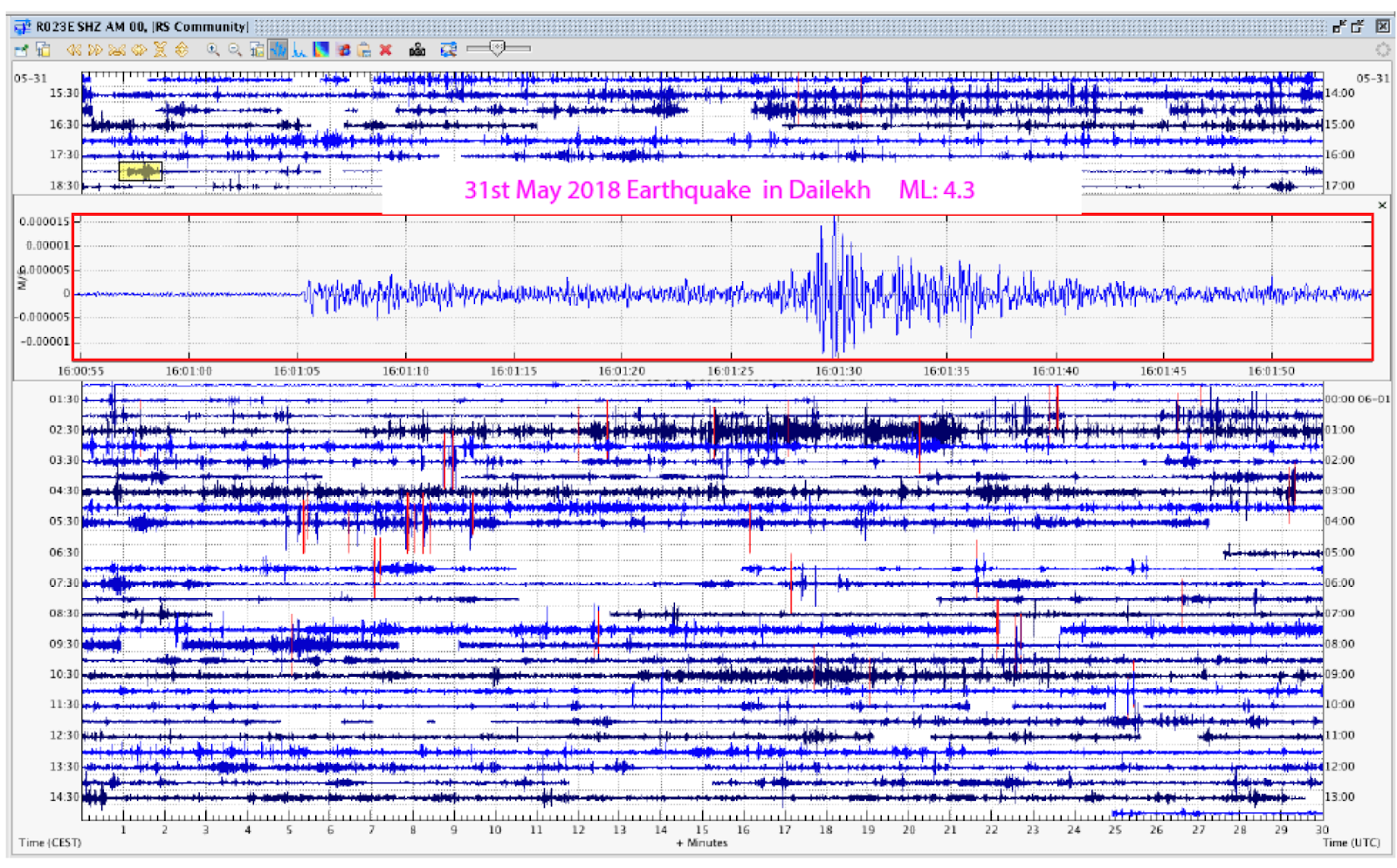

The pilot station in Baglung has already recorded various local earthquakes. We started to compare these recorded events with the seismic catalogue from the Nepali National Seismological Centre (NSC). As shown in the images below, local earthquakes have been clearly identified on the Raspberry Shake sensor. Interestingly, there are also events that are recorded in Baglung but are not in the NSC catalogue, which is encouraging for the future. This shows great potential for the school seismic network to provide useful data and to help in locating more events. This will improve the coverage and lower the detection threshold of local events, which is ideal not only for our purposes but also for scientists using the data. Ultimately, our network will ensure better preparedness of the local population by getting people involved in following seismic observations in the monitored area.

Example of waveform recorded by the pilot Raspberry Shake station in Baglung following the 2018 May 28th local earthquake, magnitude 5 according to the Nepali Seismological Center.

Example of waveform recorded by the pilot Raspberry Shake station in Baglung following the 2018 May 31st local earthquake, magnitude 4.3 according to the Nepali Seismological Center.

CHALLENGES

Besides a successful start of the Seismology-at-school project in Nepal, there are also challenges that come with the installation of a low-cost seismic network. First of all, it is not a straightforward task to get people to focus on invisible or future dangers when they are in a constant search to satisfy their basic needs, or to survive. Furthermore, the knowledge level – as well as the literacy rate – is relatively low, therefore it takes perseverance to explain earthquake processes or terms like “hazard”.

Once the community is on board, the big challenges for us are the practical and logistical conditions. Is the internet connection reliable and of sufficient bandwidth? Is there a suitable power supply? Is lightning an actual threat to the equipment? How strong is the monsoon rain? In remote areas the answers aren’t straightforward, and there isn’t a shop around to corner to improvise a solution. We plan to use alternative power supplies and perform regular visits in the first phase of the project to ensure uninterrupted data recording. Last, but not least, device location conditions must meet a “low-noise” criteria. Ground-floors and places not often used by the school – typically the storage room and office rooms, sometimes the library or labs.

Software has also proved troublesome with most computers in Nepali schools running the Windows operating system which has compatibility issues for the configuration of the sensor and the software required for real-time waveform display (for e.g. jAmaSeis). We would like to obtain a cheap computer for each school to avoid these types of time-consuming problems.

NEXT STEPS

With two Raspberry Shake stations already running in the field, and other instruments just delivered to us, we are already underway to complete the 20-station network in 2019. Visits to the agreed locations should then finalize the seed of the Nepal School Seismology Network. As there are thousands of schools across the country, we very much hope that many of them will be able to afford to purchase their own instrument. We plan to provide guidelines in Nepali for successful installation.

In the meantime, in 2019, we plan to train the teachers from the 20 initially participating schools in education activities with and around the Raspberry Shake. This includes translation of earthquake related material into Nepali, visualization of waveforms, and keeping a local “catalogue”: how much shaking was recorded locally, what magnitude was the event, at what distance? This should become an informative chart for students. When the network is complete, simple shakemaps can be plotted for local events. If all goes very well, teachers and students of higher level classes may also attempt rough earthquake locations. In any case, all these activities will increase the awareness of the local population.

With the first phase of the project running for 2 years, we hope that the teachers involved will share their experience with others. How long the seismic network and the educational activities will run in the future is an open question. We hope that the duration will be proportional to our initial efforts.

The data from our network will become openly accessible to the public. The data can then be used by scientists not only to improve catalogues, but also to refine velocity models or do other fundamental research. The high seismic activity in Nepal and the density of our Raspberry Shake network should quickly make it a useful project!

CREDITS

The initiative was launched by two researchers at the Institute of Earth Sciences, University of Lausanne, Switzerland. Shiba Subedi, originally from Mid-Western Nepal, Dhawalagree Zone, is a PhD candidate in Lausanne driving the project. He benefits from a Swiss Government Excellence Scholarship from the Federal Commission for Scholarships for Foreign Students, Switzerland. Shiba’s thesis and the initiative are lead by Prof. György Hetényi, a geophysicist working in the Himalaya since 2004. The instruments to establish the Raspberry Shake seismograph network in Nepali schools is funded by the University of Lausanne and by a Royal Astronomical Society grant.

From all of us at the Raspberry Shake team we would like to thank Shiba and György for sharing the details of their project and wish them the very best for the future of their Seismology-at-Schools program.