Things you might find with your Raspberry Shake – Part 1

January 28th, 2026

by Alan Sheehan and Philip Peake

(Some examples to help identify what you are seeing)

This blog post is all about identifying things you may detect with your Raspberry Shake using the Raspberry Shake DataView web app. If you haven’t already done so, you may like to read Raspberry Shake Basic Concepts first to understand some basic knowledge we will assume for this blog.

As the vast majority of Raspberry Shakes in service are 1Ds, most examples include the vertical geophone channel (EHZ or SHZ). Obviously, the other 3D and 4D Shakes (horizontal) channels can also detect these events. Some examples of infrasound detections are also included for Raspberry Shake and Booms.

DataView

Multiple programs and presentation styles exist for the data gathered from sensors measuring ground movement. As mentioned, in this document, we will focus on Raspberry Shake DataView, a web-based software that has access to the archived data of all Raspberry Shakes and displays it in (very close to) real-time.

This can be accessed at:

https://dataview.raspberryshake.org/

This will display a list of online Raspberry Shakes on the left, together with a blank window panel. Expand one of the Shakes in the list, and you will see a list of its different channels.

Each channel is associated with a sensor managed by the Raspberry Shake. Most have only one (EHZ), which measures vertical movement in the Z axis (up and down). There are also Raspberry Shakes, which have sensors measuring in three axes (X, Y and Z) with the horizontal X and Y axes that are aligned in the N-S and E-W directions. And, there may also be an HDF sensor, which measures very low-frequency air pressure changes (infrasound).

A complete list of all channels and their acronyms can be found here:

| Channel | Description |

|---|---|

| SHZ / EHZ | Vertical geophone channel (up-down weak motion) |

| EHE | East-West geophone channel (longitudinal weak motion) |

| EHN | North-South geophone channel (latitudinal weak motion) |

| ENZ | Vertical accelerometer channel (up-down strong motion) |

| ENE | East-West accelerometer channel (longitudinal strong motion) |

| ENN | North-South accelerometer channel (latitudinal strong motion) |

| HDF | Infrasound RSBOOM channel (air pressure differences) |

Typically, you might access DataView by providing the name of your Raspberry Shake and the sensor you want to view. Example of my Shake:

https://dataview.raspberryshake.org/#/AM/R309F/00/EHZ

Name: R309F

Sensor: EHZ

If you haven’t done so yet, it is well worth your time to click on the red question mark at the top right of the DataView window to tour the system.

Earthquakes

The most common cause of earthquakes is the movement of tectonic plates. As the plates of the Earth’s crust move past each other, they can interlock, and they can also stick to one another due to friction. As the plates continue to move, but the edges stay in contact, stress builds up until the edges move past each other suddenly, releasing the stress and resulting in an earthquake.

Other sources of earthquakes include volcanism (eruptions and development of magma chambers), explosions, and other mechanisms that can distort and/or fracture rock. Earthquakes from these sources are usually smaller than those from tectonic sources.

The earthquake produces two types of vibration, which propagate through and around the world as waves: P waves and S waves (there are others, such as surface waves, but we are not focusing on them in this blog post).

P waves are compression waves (similar to sound waves in air) that travel through the Earth.

S waves are shear waves as a result of the shearing of rocks in the earthquake.

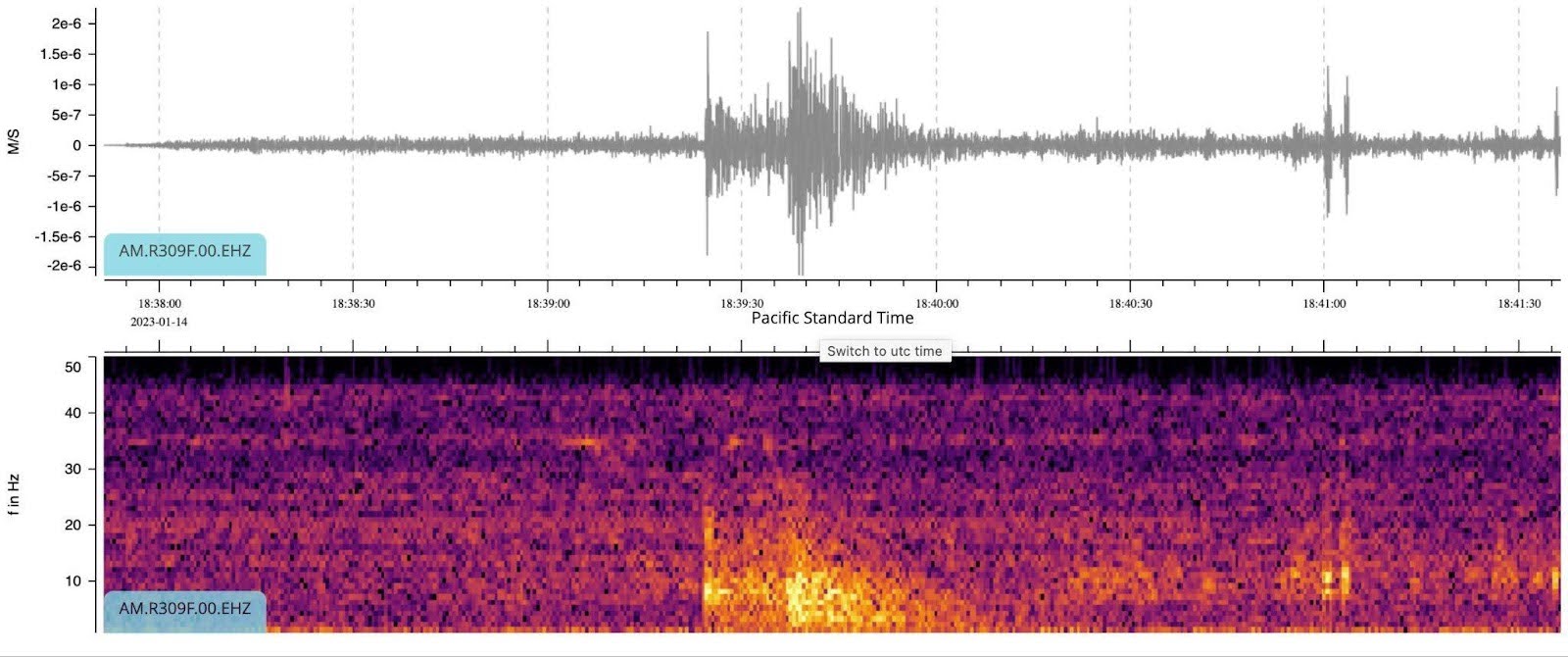

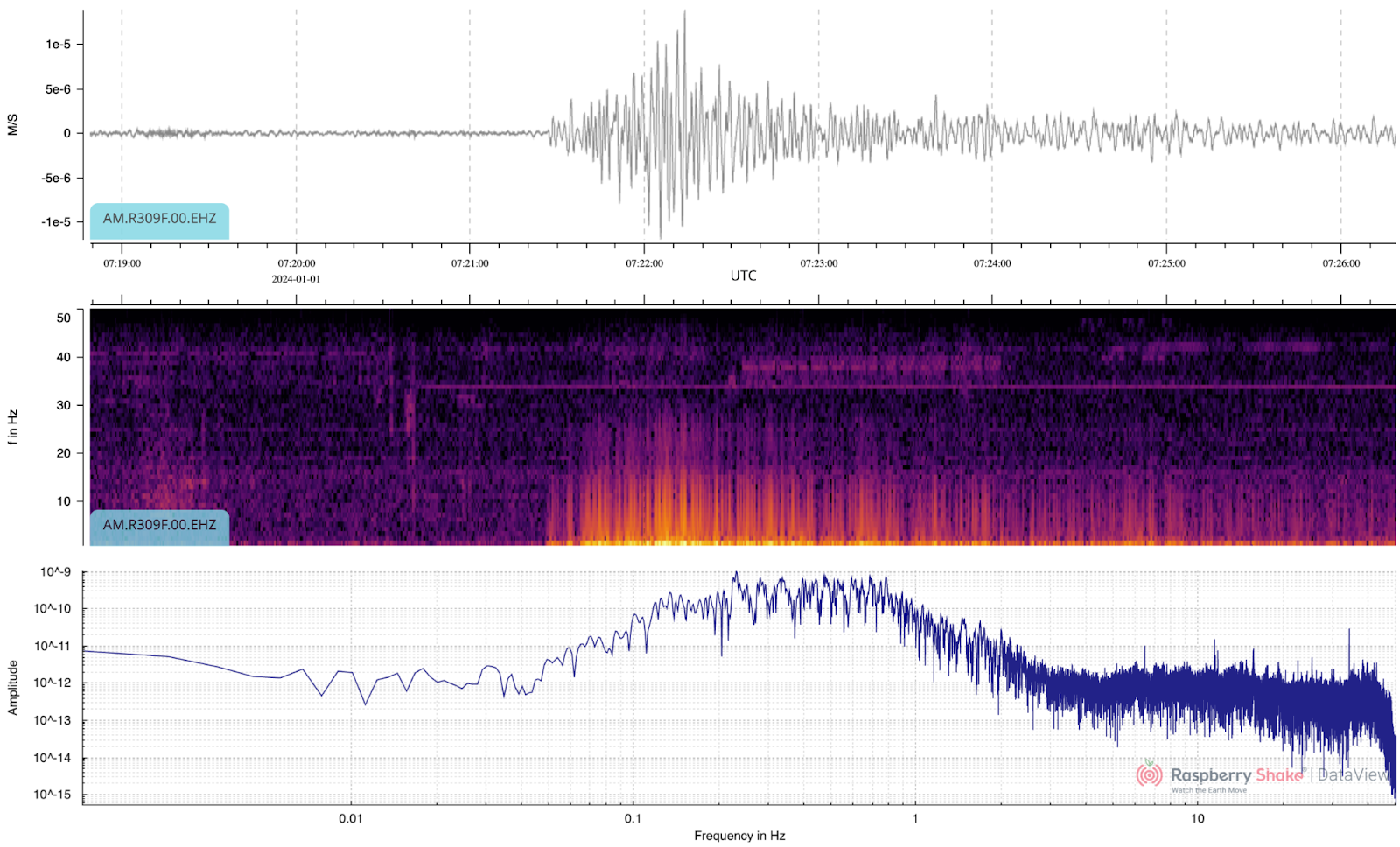

The P wave moves faster than the S wave (P = Primary, S = Secondary). The further away from the earthquake, the larger the gap between the P and S waves. Typically, the S wave is much more destructive than the P wave. What this might look like is illustrated in the screenshot below (Figure 1).

Note that most of the energy from an earthquake is at very low frequencies (higher intensity is shown as higher brightness in the frequency plot). The two waves (P, S) show clearly in the frequency plot, with sharp “edges” for the arrival of each one.

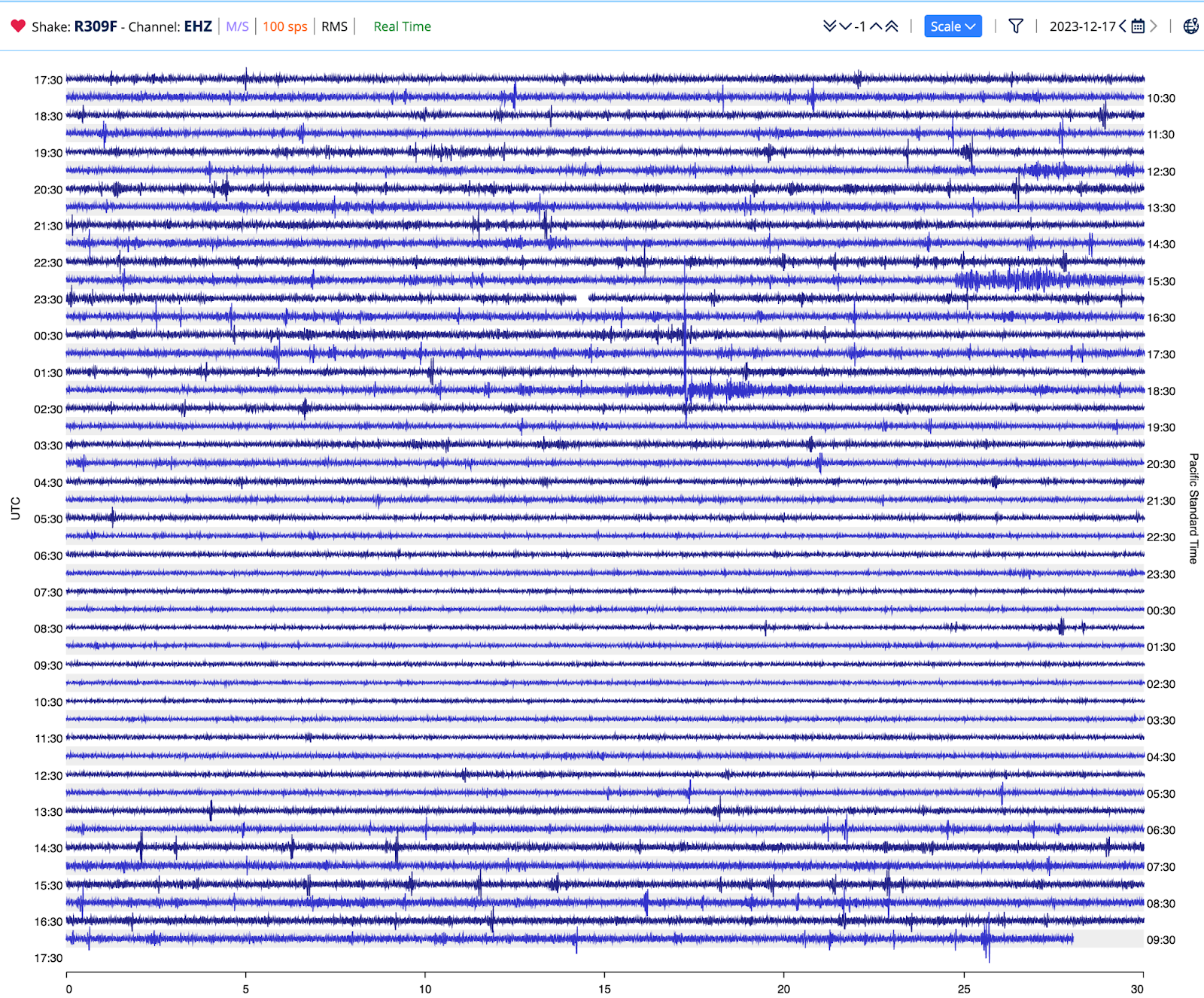

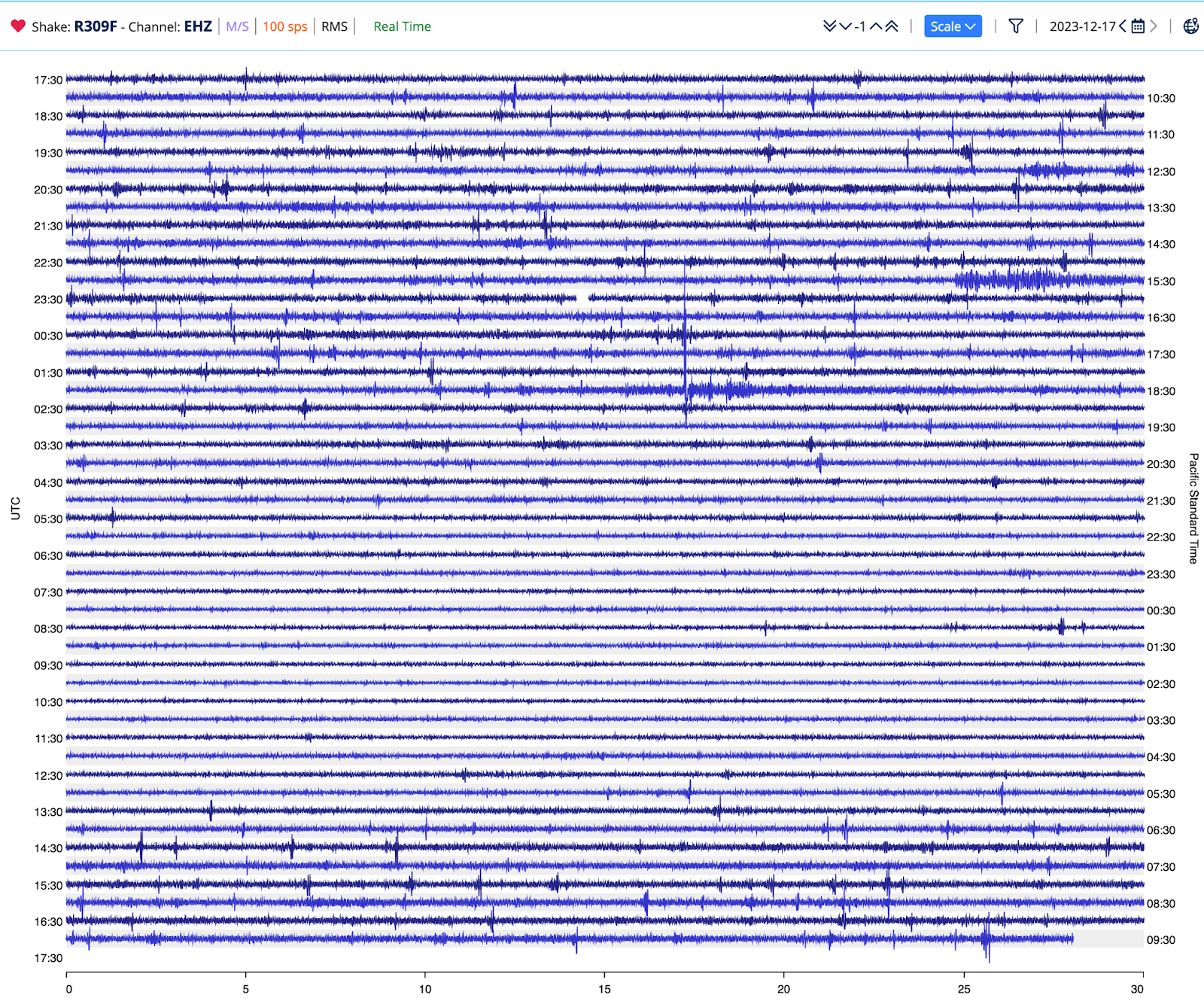

This illustration is of a fairly local earthquake. A more distant one is actually present on the helicorder screenshot below. Look at the right-hand side, the line labelled 15:30 Pacific Standard Time (Figure 2):

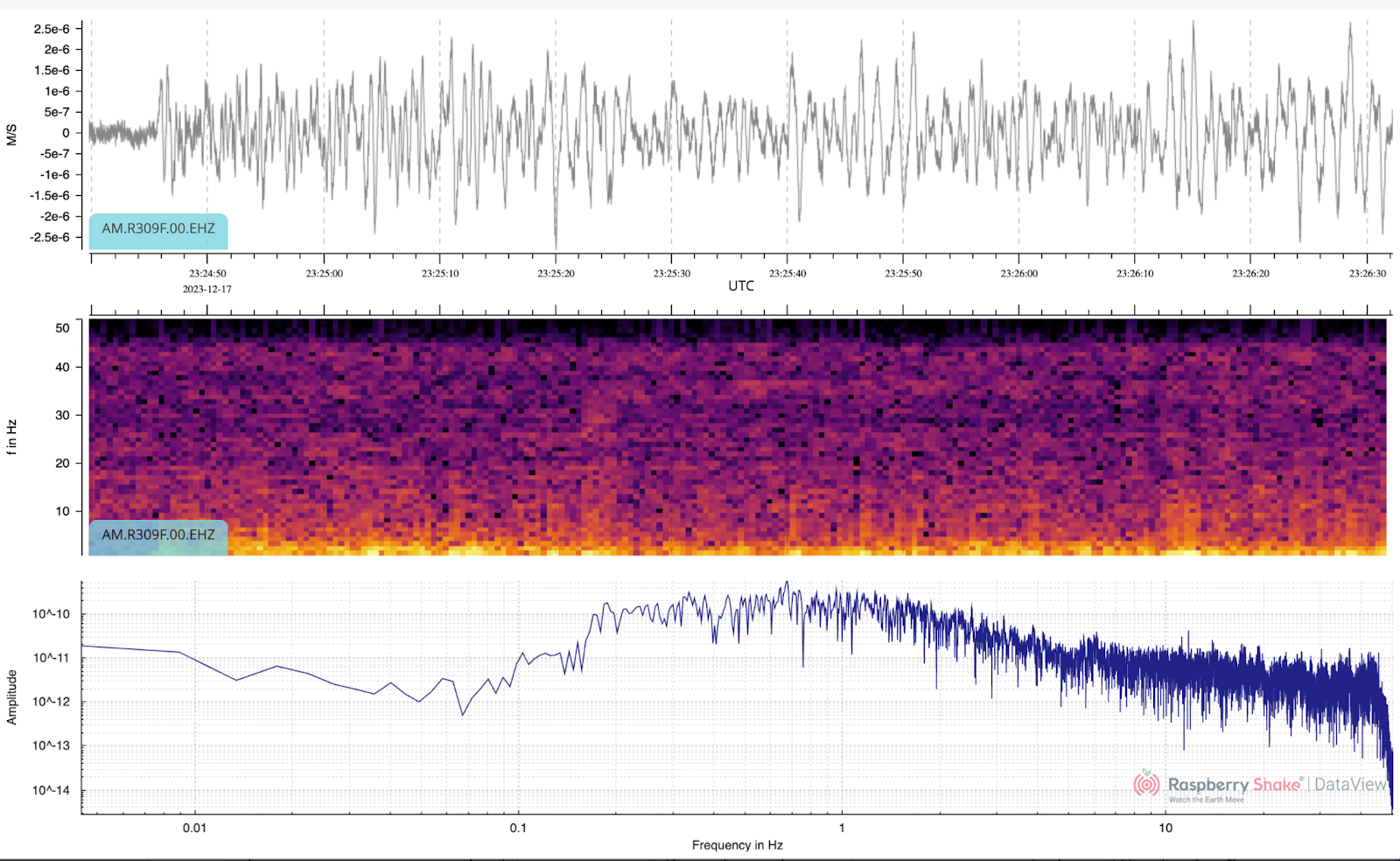

How can we tell this is an earthquake? Take a look at the expanded view (Figure 3):

Two elements stand out:

- The helicorder trace is low frequency (<5 Hz), and you can see the discrete up/down excursions rather than a more general “fuzz” that would be typical of a human-caused trace and higher frequency on the frequency display;

- The power density graph shows most energy below about 2Hz.

This was actually a 4.6 magnitude earthquake in Canada, about 650 km away from this seismograph located in Northern Oregon.

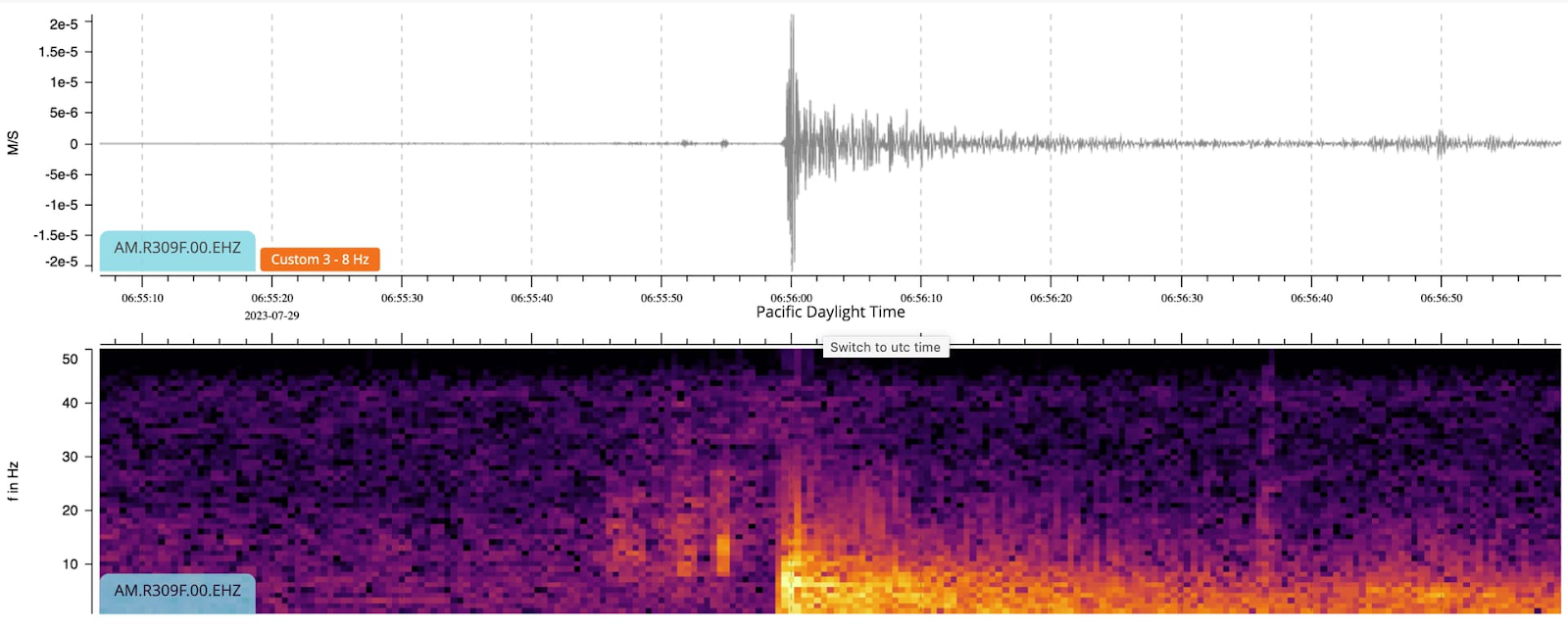

More typically of closer earthquakes, you would see a better-defined trapezoid shape to the trace as the “echoes” die away and a similar shape to the frequency display (Figure 4):

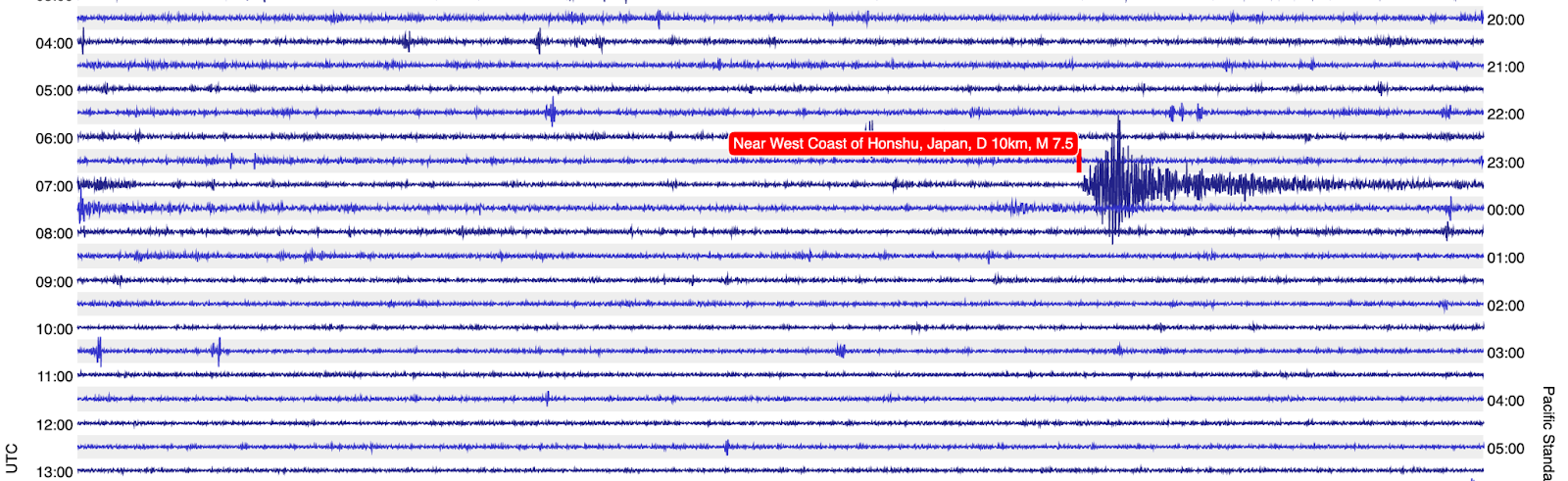

Just occasionally, you will see something like this when you take a look at your helicorder trace while sipping your morning coffee (Figure 5):

That earthquake was nearly 8,000 km away. If the timing and profile match a large event and the signal is strong enough at your Shake, the Data View software conveniently tags it for you.

Note that with larger earthquakes (Figure 6), even distant ones, the energy is mostly at very low frequencies, as we have already seen, but there are some noticeable higher frequencies.

It is the distance that matters here, as higher frequencies are more readily attenuated (reduced in amplitude) with distance. Very close earthquakes, regardless of size, will show a strong signal across all frequencies.

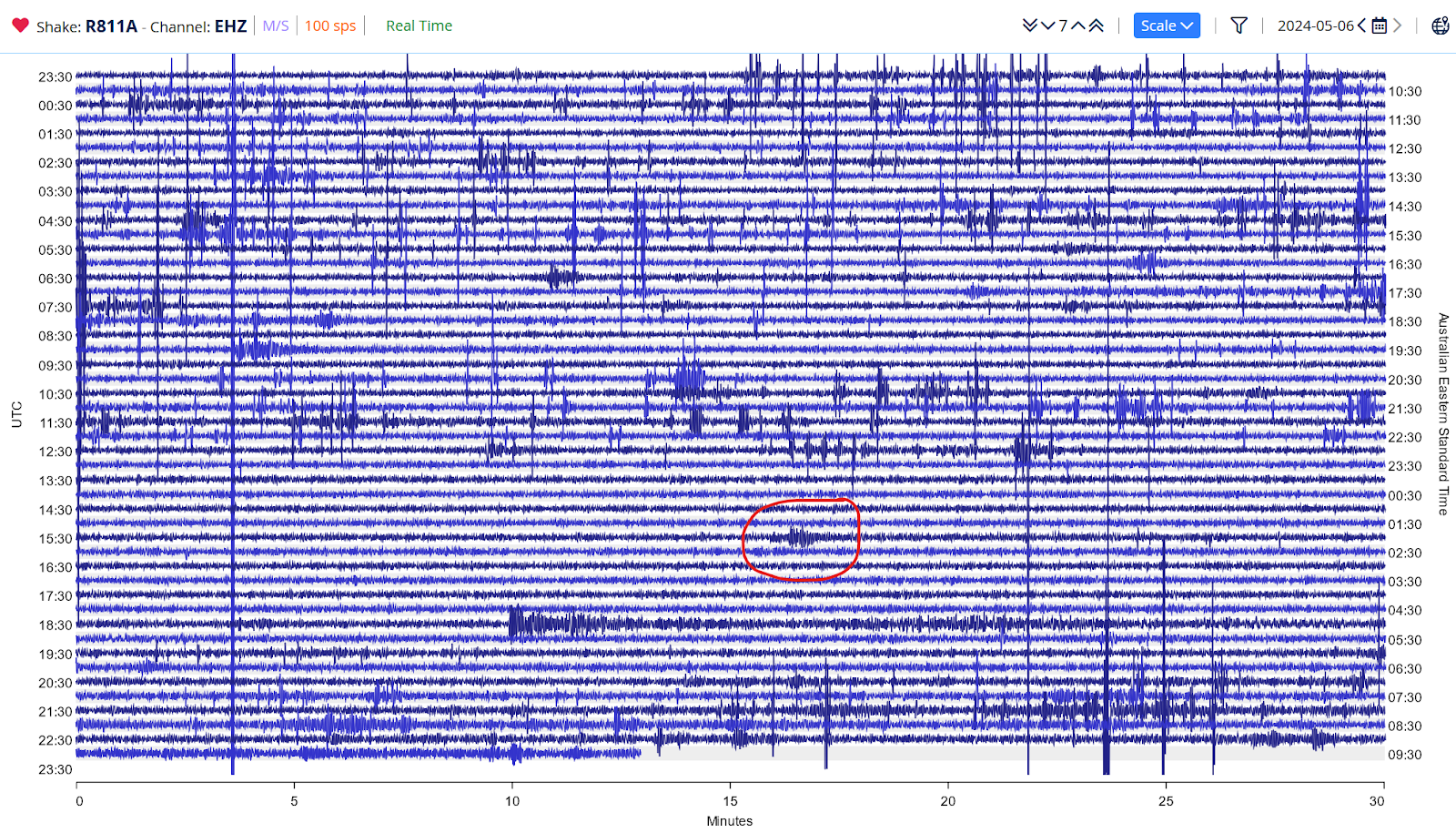

To illustrate the point, here is a rare (I think) example. The event circled in the helicorder plot below looks like a small local earthquake or mine blast with an apparent P arrival followed closely by a larger S arrival (Figure 7):

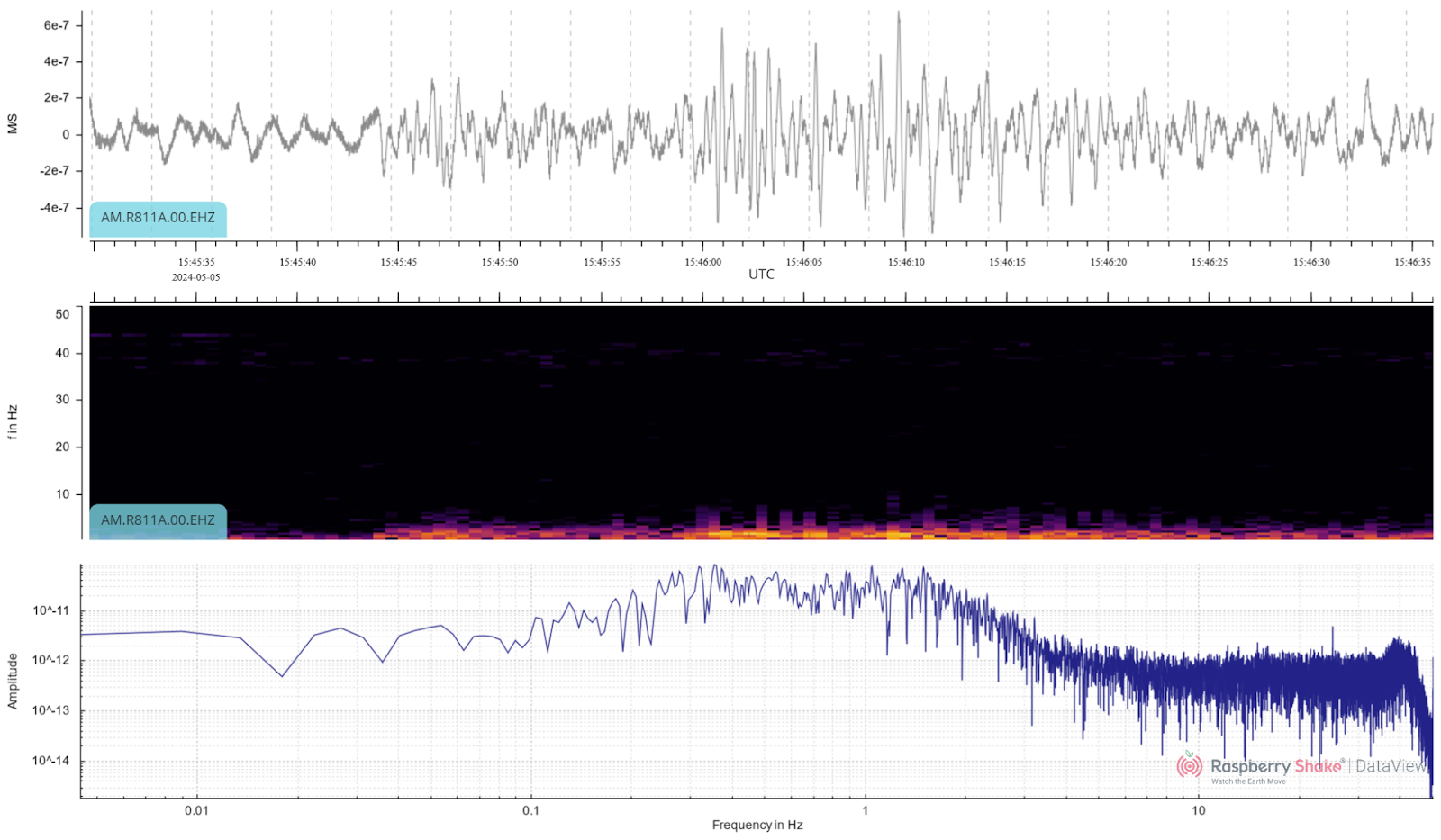

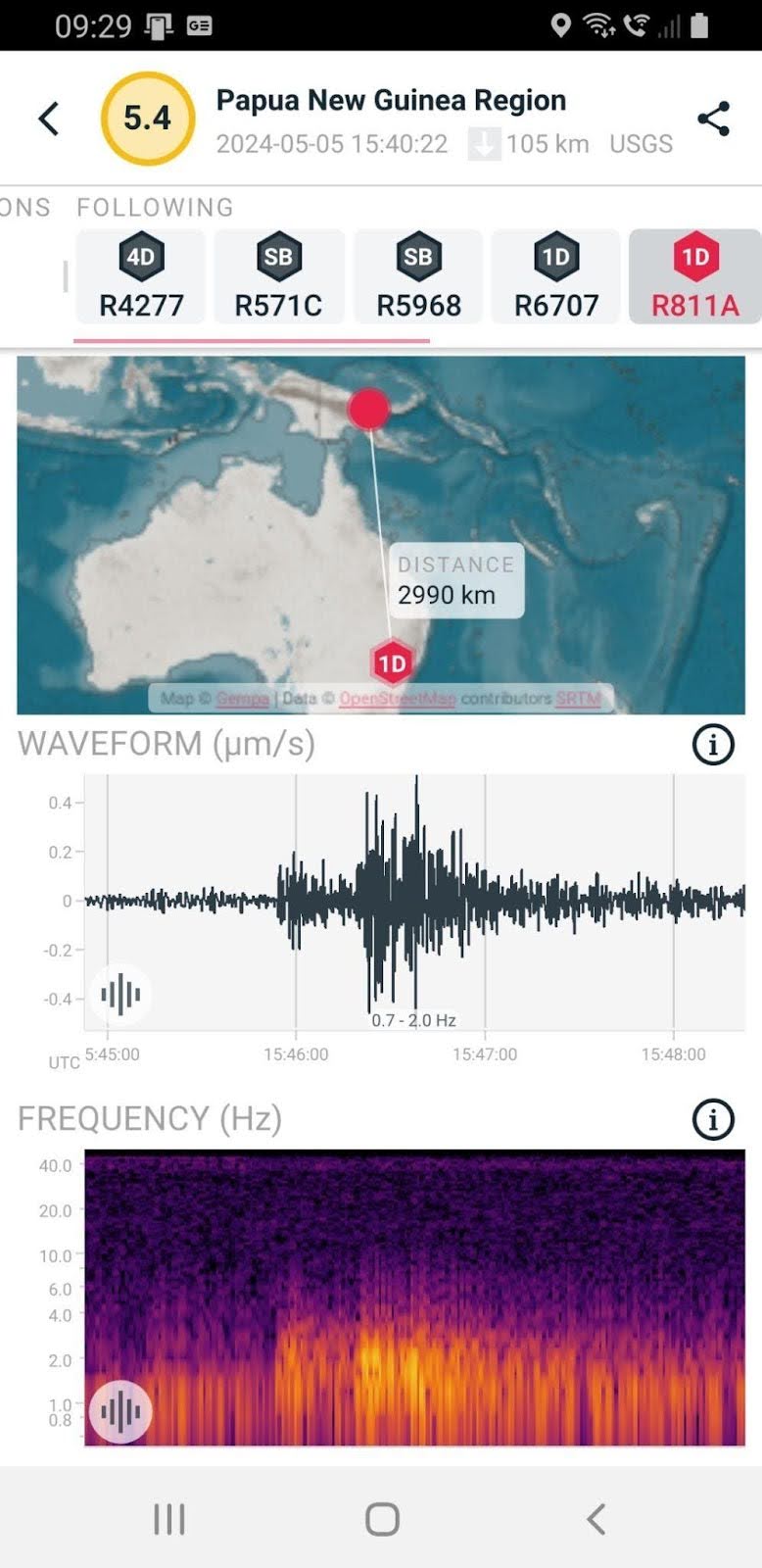

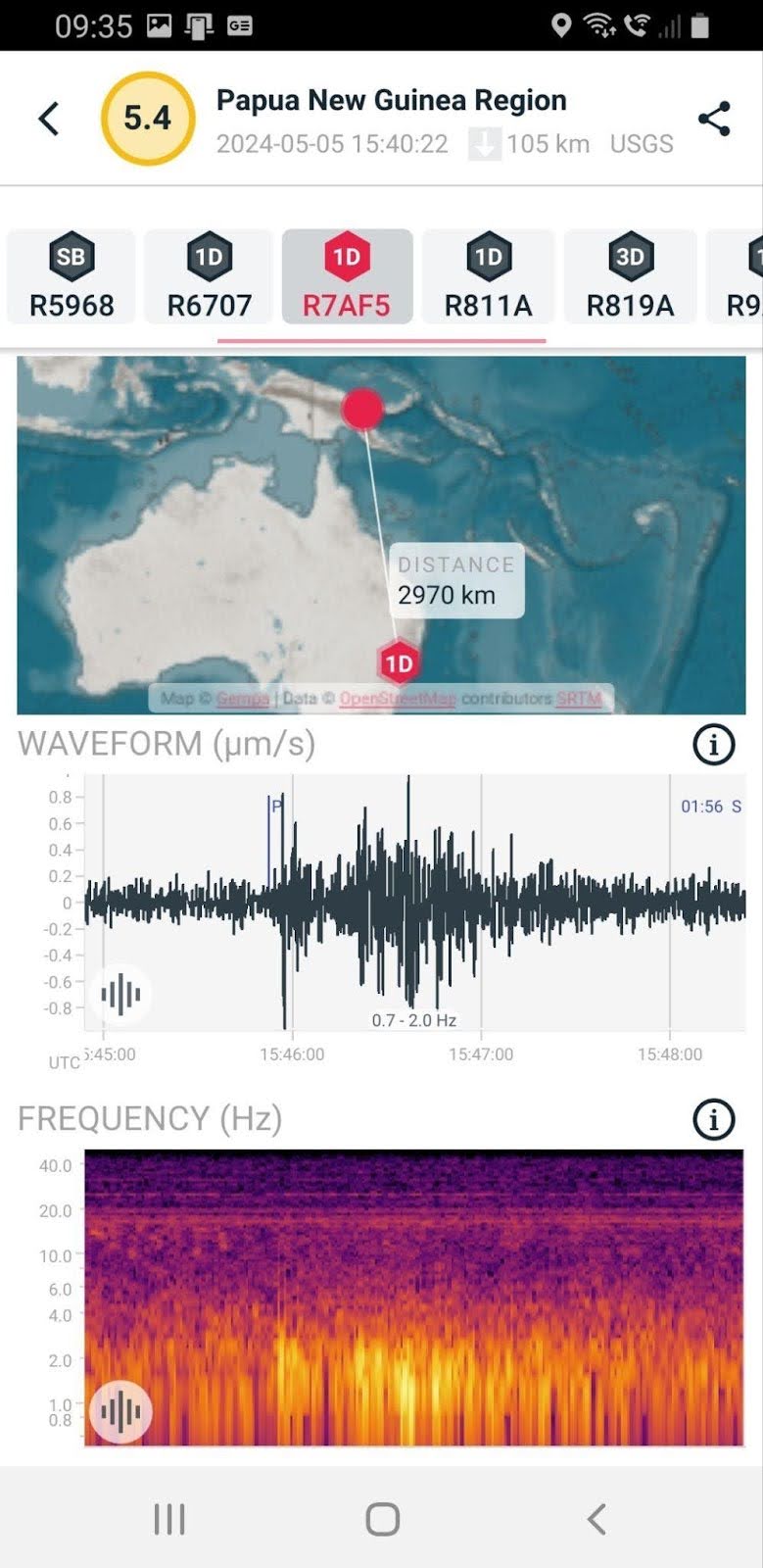

Closer inspection, however, reveals this (Figure 8):

The P phase arrival is at 15:45:44 UTC, and there would appear to be an S arrival at 15:46:00 UTC as if it were a closer earthquake (just 130 km away).

However, there are no frequencies above about 4 Hz in the spectrogram, and the PSD (Power Spectra Display) is flat above 4 Hz. A close earthquake would show some higher frequencies in the typical triangular fading shape.

This is actually just the P arrival of an Earthquake 2990 km away in the Papua New Guinea region – hence the lack of higher frequencies. This was confirmed by comparing other nearby Shakes and checking ShakeNet to ensure that no other earthquakes were close in time to provide the apparent “second arrival” (Figure 9).

Because P and S waves travel faster the deeper they go, the P and S waves tend to travel in curved paths below the surface of the earth. Waves from close earthquakes don’t go very deep before they come up to the seismograph, but waves from distant quakes do go quite deep and approach the seismograph from a steeper angle.

This means that close earthquakes appear in the vertical EHZ channel as a reasonably strong P wave but an even stronger S wave closely following it. As the waves’ approaches are quite flat, most of the P wave results in sideways movement that would show up on the horizontal (EHN and EHE) channels of a 3D shake, but because the quake is close, the vertical component of the P wave is still reasonably strong.

The S wave approach is also quite flat, but the amplitude is larger in the EHZ channel, as it is a transverse wave, so most of the movement is perpendicular to direct travel, so the S wave appears larger than the P wave in the EHZ channel for close quakes.

For distant quakes, the waves go deep and approach steeply. This causes most of the P wave to result in vertical movement, which shows well in the vertical EHZ channel, and is very weak in the horizontal (EHE and EHN) channels of a 3D shake. Likewise, the S wave results in mostly horizontal movement as the wave approaches steeply from below. Hence, the S waves are weak in comparison to the P wave in the EHZ channel but much stronger in the horizontal (EHN and EHE) channels.

As a result, the signature for a close quake is:

- A moderately strong P wave with a sharp leading edge and strong low frequencies in the EHZ channel;

- A very strong S wave with a sharp leading edge and strong low frequencies in the EHZ channel;

- Not much time delay between the P and S waves;

- Both P and S waves will show higher frequencies in the PSD, FFT, and spectrograms than distant quakes;

- P wave is likely to be stronger in the horizontal (EHN and EHE) channels than in the EHZ channel.

The signature for a distant quake is:

- A strong P wave with a sharp leading edge and strong low frequencies in the EHZ channel;

- A weak S wave in the EHZ channel, which is significantly delayed from the P wave;

- The P wave will be weak in the horizontal (EHN and EHE) channels;

- The S wave will be much stronger in the horizontal (EHN and EHE) channels than both the P wave or the S wave EHZ signal;

- Most higher frequencies are attenuated (i.e., the high frequencies are more easily absorbed and scattered by the rock than the low frequencies).

Diurnal Variation

One of the first things that usually stands out as you look at the helicorder plot is the diurnal variation. That is, the difference between night and day.

This becomes more pronounced the closer you are to civilization. Heavy traffic, railroads, building work, demolition, and many other things shake the earth, and those vibrations affect seismometers for many miles around. Perhaps the most important of the natural causes of diurnal variation is wind. Often, there is more wind during the day and less at night. This can be more pronounced in some places than others, for example, due to sea breezes. See the screenshot below – local time is on the right (Figure 10).

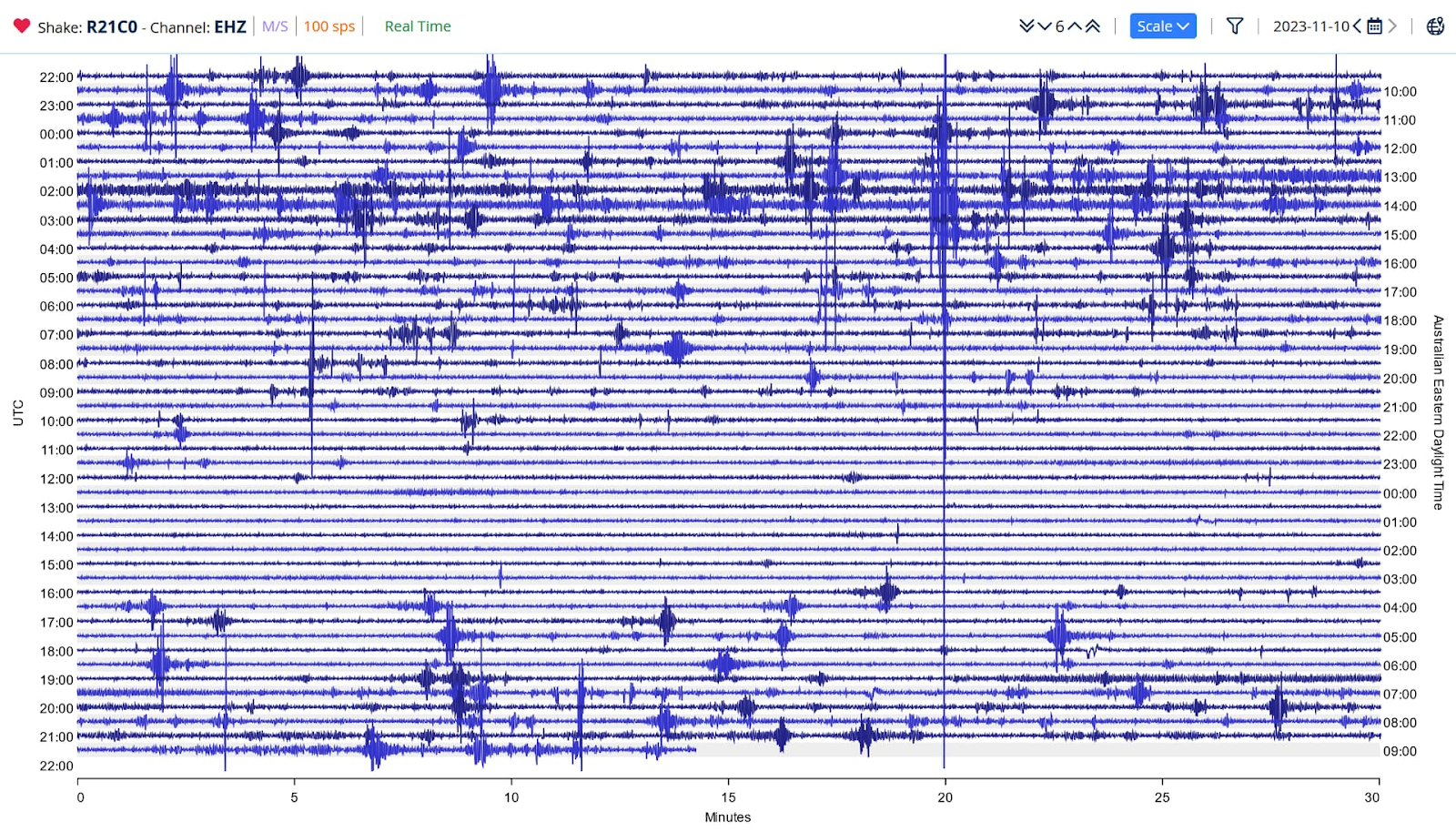

Not all Shake installations are ideal. You may not be able to find or achieve a truly “quiet” site for your Shake, so your helicorder may show more local noise. This is usually referred to as Cultural Noise. For example (Figure 11):

This helicorder plot shows more cultural noise. The station is installed inside a house on the concrete ground floor. Most of the “blobs” of the helicorder are passing trucks.

Big doesn’t always mean important

A good reminder before we close is that, for something to be big on the helicorder, it has to be either VERY big in the real world, or very close to the Shake. Big things rarely start and stop moving very quickly, so big spikes are almost definitely something close.

Most times, we aren’t interested in them. So, no doubt, you have immediately noticed the huge spike at 02:50UTC in the helicorder plot above (Figure 11). It’s easy to think a big spike must be something important, but in fact, it’s not. This huge spike trying to grab your attention is just noise.

Wrapping up

By now, you’ve seen how earthquakes leave distinctive fingerprints in seismic data, from the sharp arrival of P and S waves to the way distance reshapes frequency content and timing.

You’ve also learned why your Raspberry Shake is rarely quiet during the day, and why large signals are often local noise rather than something geologically significant.

These fundamentals form the backbone of signal identification. Once you can recognize what a typical earthquake and what normal background noise looks like at your station, everything else becomes easier to interpret.

But earthquakes are only part of the story.

Coming up in Part 2…

In the next article, we move beyond tectonics and into some of the most surprising signals your Raspberry Shake can detect. You’ll see how to identify:

- helicopters and other aircraft

- sonic booms from supersonic jets

- atmospheric explosions and lightning

- meteors, fireballs, and space junk re-entries

- mine blasts and other human-made explosions

Many of these events can look dramatic, and some can even resemble earthquakes at first glance. Understanding their unique signatures will help you avoid false identifications and, just as importantly, recognize something genuinely unusual when it happens.

Stay tuned!