PARSLEE: THE OPEN SOURCE ROVER WITH RASPBERRY SHAKE ON-BOARD – PART 2!

15 April, 2020 – by Dr. Jamie Molaro

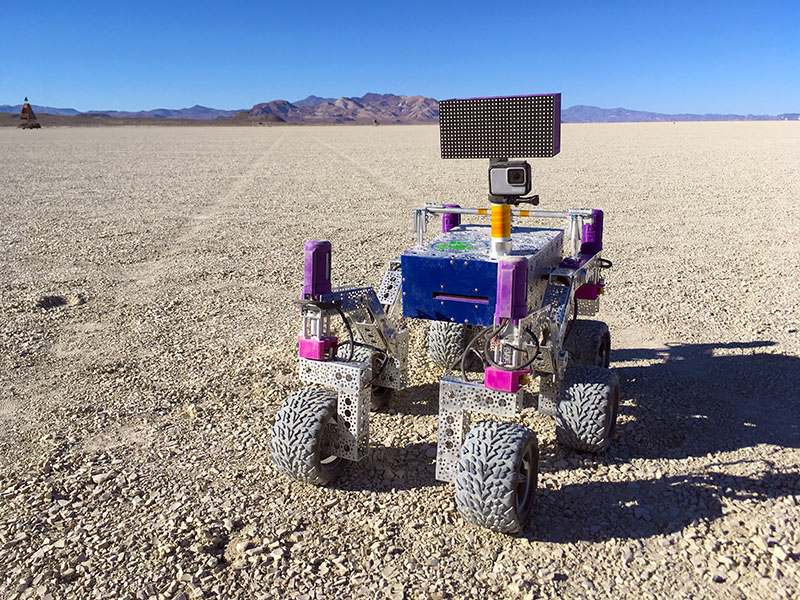

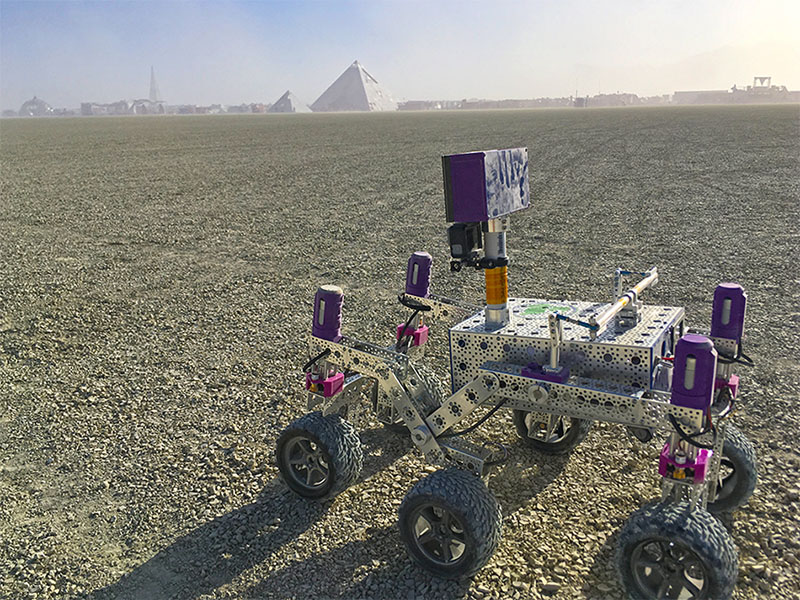

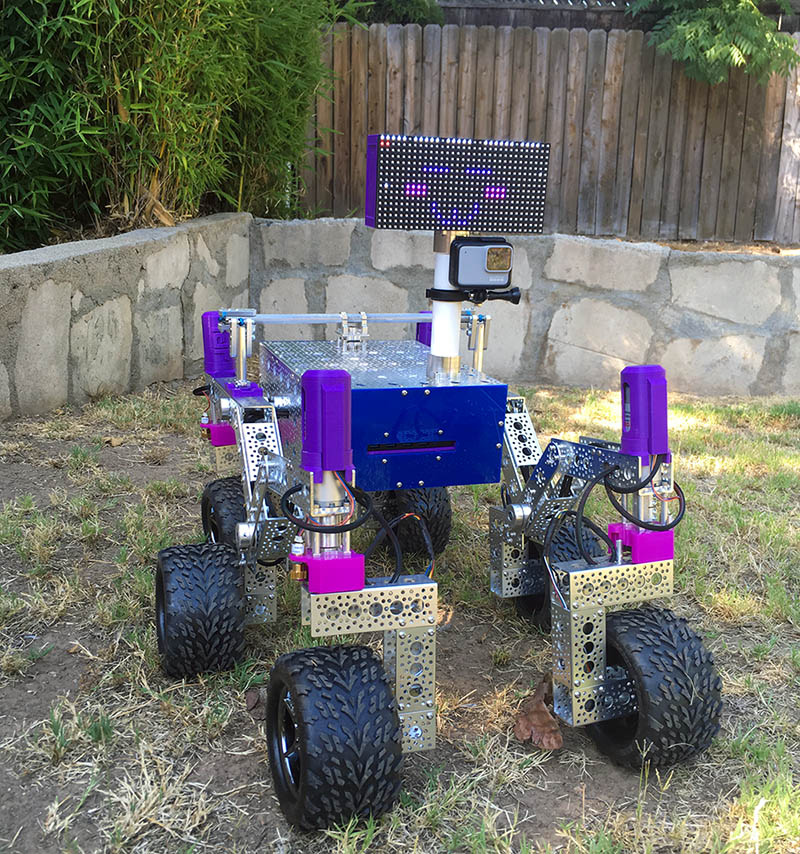

Since our last blog post, my husband and I have finally finished building our Open Source Rover named PARSLEE (for Planetary Analog Remote Sensor and ‘lil Electronic Explorer), with our Raspberry Shake onboard.

It ended up being a much more challenging and time-consuming project than either of us anticipated. It was a rewarding challenge, and certainly a learning experience, but also stressful and frustrating at times. We got a lot of the rover built and put together fairly easily, but we did hit some pretty major roadblocks to finishing. You can read about the entire build here.

WHAT WAS IT LIKE TO BUILD THE ROVER?

If I had to boil down our entire experience to two main points it would be these:

a) Learning things is hard, and no matter how smart you are, doing something new always comes with a learning curve.

b) Working on an open source project can provide challenges all of its own.

To point (a), we spent a lot of time doing things wrong, redoing things, and figuring out how to do new things, and there were parts of the project that we needed both time and help from others to get through. When you’ve never done something before, this is expected! Ultimately, that’s what science and engineering is, what learning is. While the project was frustrating at times, I was prepared to deal with this as a natural part of the process, just like I do in my work as a scientist.

To point (b), I think the hardest thing about building the rover wasn’t any one particular roadblock (though, we did have *quite* a time trying to figure out why our corner steering motors kept failing…), but this is one of the challenges you face when working on a project in active development.

The advantage to working on an open source project, of course, is that it can be improved by community input. Our experience working in the rover building community was great. It was very active and collaborative, and builders were constantly coming up with ways to address build issues, redesign components, and discuss future improvements. The downside is that the folks running the project have a limited amount of time to actually work on it, and as a result the documents were in an active state of evolution all summer as we built PARSLEE. This led to numerous occasions where we were following partly new and partly old instructions, which naturally led to a lot of mistakes and time spent trying to understand where we went wrong. Or sometimes a new solution would be in development on the forum, but the community had not yet reached a consensus, causing us to delay in finishing certain parts of the rover and getting behind in our schedule.

There is no great way around these types of issues, so it was just a fact of the build and the current state of the project at that time. While frustrating at times, the upside was that the project developers and the other builders were really supportive and everyone seemed willing to help each other out. We all get stuck sometimes, and there was always someone there to help us out when we needed. Plus, we learned a lot of useful things generally by monitoring discussions between makers farther along in the project or who had more experience with robotics than us. In this sense, I’m appreciative of all the support we’ve gotten from a great community, and the learning opportunities we had not anticipated when we started the project.

At the end of the day, we would not have been able to build PARSLEE without that community! Next time, we just need to make sure we give ourselves a less ambitious timeline 🙂

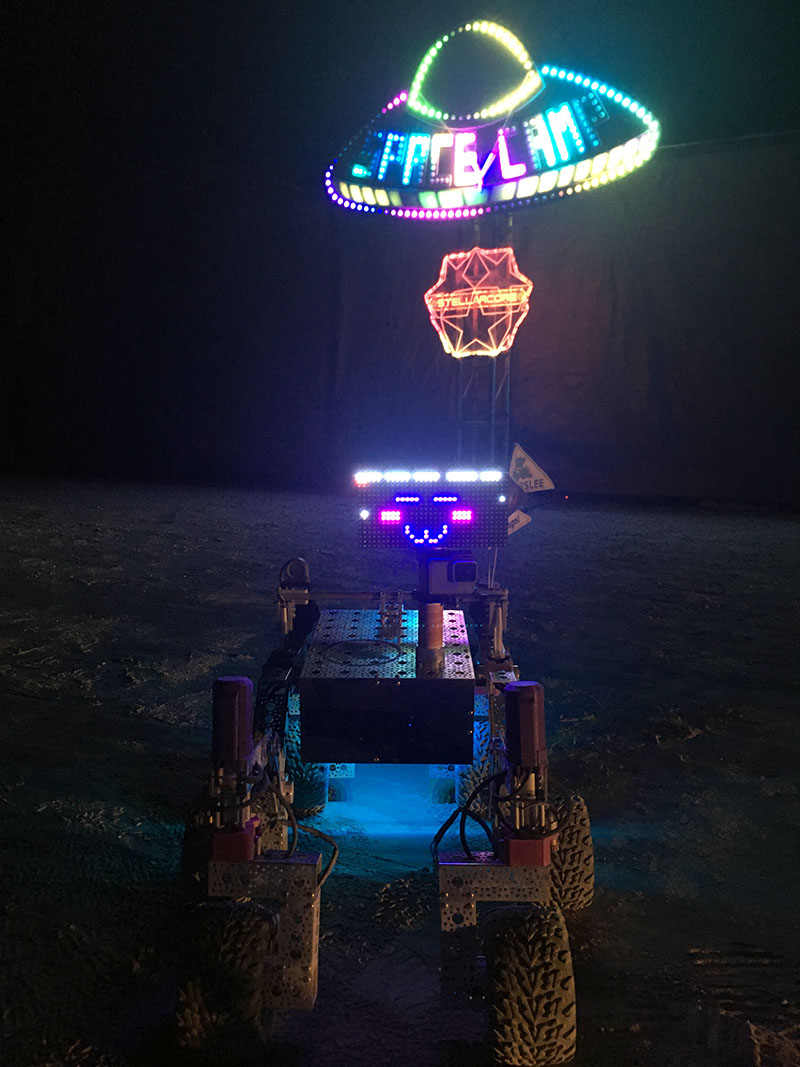

PARSLEE IN THE DESERT

Our goal was to finish PARSLEE in time to bring it out to the Burning Man art festival.

We had a fantastic time and everyone we met loved PARSLEE! We took it to all kinds of different camps and met lots of interesting people who were excited to learn about the rover and about space exploration. We’ve been going to Burning Man for about 15 years, and one of the things that really makes the event unique is the harsh desert environment. What inspired us to build the rover is that the landscape is actually a lot like Mars! It’s warmer, and certainly easier for us to breathe, but the landscape is a similar mix of dry playas and dusty terrains, interspersed with rocks and mountains.

There are also dust storms and dust devils all the time, which add an element of surprise and discomfort sometimes when you least expect it. We call these kinds of environments planetary analogs, because they are similar enough to other bodies to enable us to do research and test technology but obviously much easier to reach and work in than actual extraterrestrial surfaces. Plus, it’s really beautiful out there and everyone we met commented on how well suited the desert was as a rover backdrop.

Everywhere we went, PARSLEE piqued people’s curiosity. They came to talk with us about the rover, asked questions about planetary explorations and current NASA missions, wanted to learn about the engineering of the rover, and asked to test drive it. As an outreach effort, it was wildly successful!

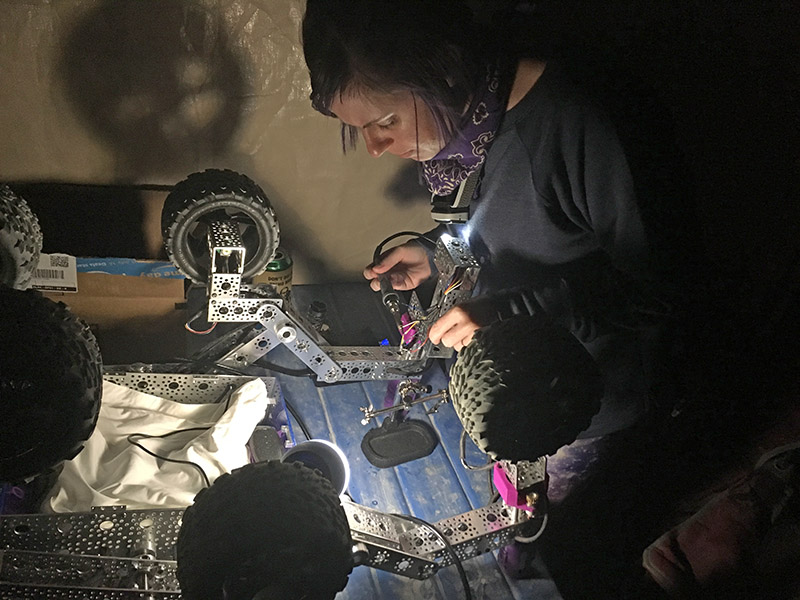

We were also very proud of ourselves that we only broke the rover three times! This is half-jest, of course, but if you’ve ever been to the event, you know that the Black Rock Desert is a physically harsh place to survive. We expected we might run into some mechanical problems with PARSLEE while we were out there. This, too, is a natural part of the science and engineering process, and there is nothing like soldering a new motor into a robot behind a dive bar in the middle of the desert to make you feel really capable and proud of everything you’ve learned.

We had to replace one of the motors due to a pothole-related incident, and we also had problems with one of the legs falling off. The latter turned out to be a design issue. Since the motor shaft is only coupled to the leg via a clamp, we think the vibrations from driving on the bumpy, gravelly terrain just caused it to keep coming loose.

We would never have discovered this issue at home driving it around our house, so it was a valuable thing we learned from the trip. We’re going to look into how we can redesign this part of the rover to make it more robust for future trips.

COLLECTING DATA WITH PARSLEE

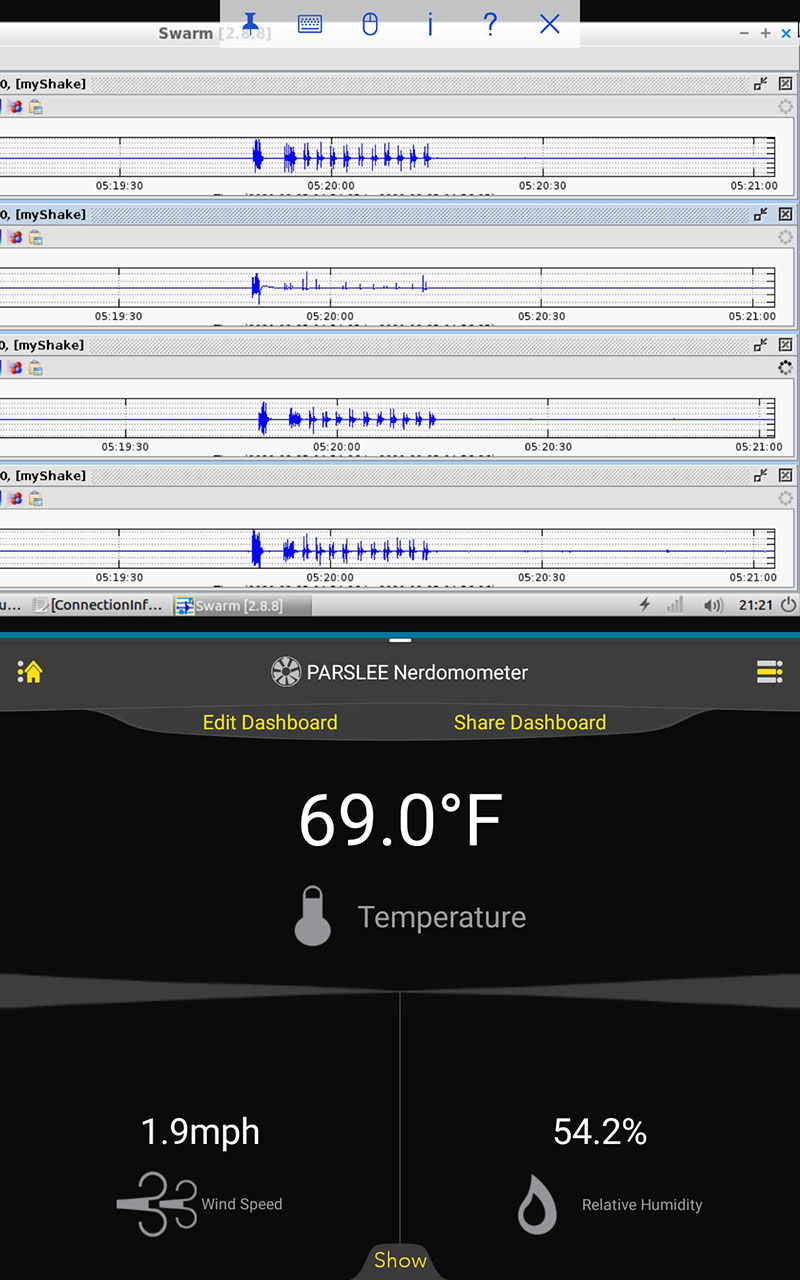

One of the ways that we tried to interact with people using PARSLEE was with a tablet that displayed the data output from the camera, weather meter, and Raspberry Shake seismometer on board.

People are generally less interested in data than they are in robots, but we wanted to take the opportunity to introduce people to how we use data to explore. The camera worked the best, and people enjoyed trying to drive the rover around only using the tablet as a visual.

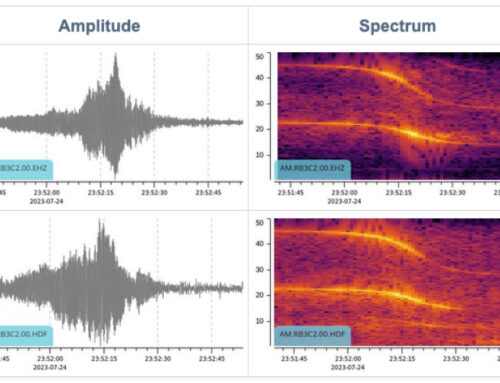

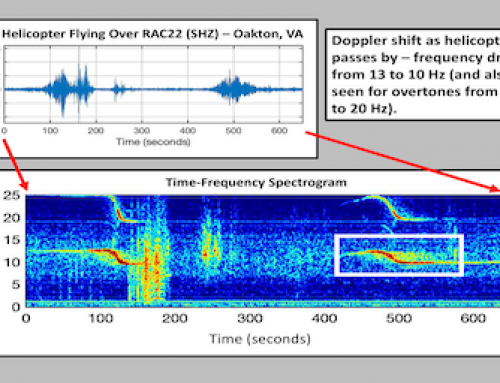

The weather station also caught people’s attention, particularly when it was extra hot or windy. The Raspberry Shake also worked perfectly, but unfortunately did not give us the result we had hoped for. There are a lot of camps with loud sound systems at Burning Man, and we thought that if we were close enough we could pick up the signal of the music on the Shake.

PARSLEE’s dashboard display on the tablet

What we hadn’t considered was that the rubber wheels of the rover would be really isolating. So much so, that we didn’t actually pick up any signal on the Shake except for from the rover moving itself. All the other signals coming through the ground were dissipated in the wheels. This is another example of why we test technology before sending it to another planet! It is, again, just a natural outcome of any engineering project. Sometimes you just don’t know what is and isn’t going to work until you try it out. For this year, we’ll have to build it a little deployable arm to lower the Shake to the ground.

QUAKES IN SPACE!

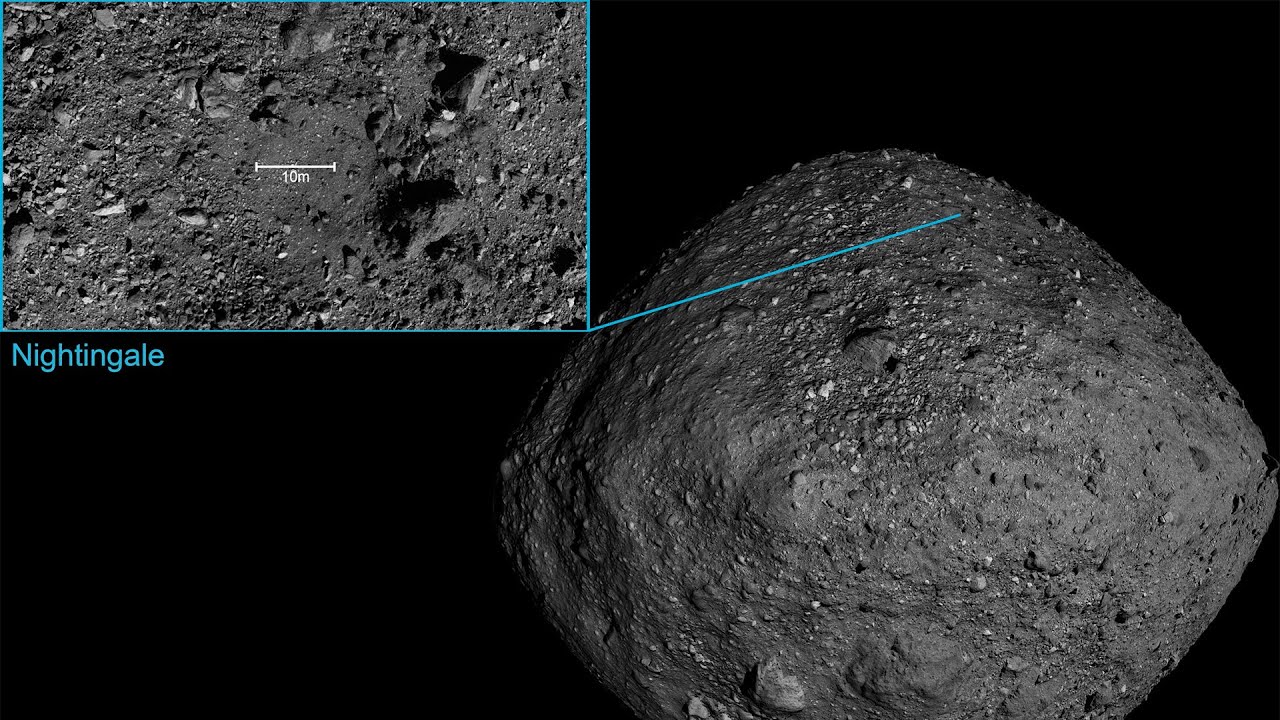

On that note, I’d encourage everyone to check out the latest news from NASA’s InSight and OSIRIS-REx missions. InSight is a Mars lander spacecraft with a seismometer for detecting Marsquakes. The data it is collecting not only show the first quakes ever detected beyond Earth and the Moon, they also provide invaluable information about the planet’s interior and active fault systems. OSIRIS-REx is an asteroid sample return mission, meaning it’s been tasked with collecting rocks from the surface of the asteroid Bennu and returning them to Earth. I am a part of the OSIRIS-REx science team, and we’ve been working hard all year analyzing images of Bennu’s rocky surface. Below is a picture of the site selected to collect our sample, named Nightingale [Credit: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona]. (All the asteroids features are named after birds, check out my embroidery of all four candidate sample sites.)

The “Nightingale” site on the asteroid Bennu. Credit: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona

One of the most interesting discoveries we’ve made at Bennu is that small pebbles are being ejected from the surface! The asteroid is what we call a microgravity environment, that is it’s so small (only about a half mile wide) that its gravitational force is low enough to make ejecting stuff from the surface pretty easy. So most of these particles completely leave the asteroid’s system, though others fall into sub-orbital trajectories and eventually fall back down onto the surface. But what is causing this phenomena? Well, the process I study is called thermal stress weathering, the fracturing and mechanical breakdown of rocks into dust from stresses caused by heating and cooling. It’s the same idea as when you leave something out in the sun for a long time and it breaks down, only in space the heating and cooling it experiences is much more intense. This causes boulders on the asteroid surface to shed material through a process called exfoliation, and we think that particles get flung off the surface as this occurs. I have a scientific publication coming out on this soon, so keep your eyes peeled for news.

Some colleagues and I have been discussing how much we could learn about the properties of the asteroid’s boulders and its interior if we had a seismometer on the surface. I have some funds to do laboratory testing of heating and cooling rocks in a vacuum chamber to study how quickly fractures develop in planetary environments. I’m going to try using the Raspberry Shake inside the vacuum chamber so that I can detect emissions from the fracturing events at the same time. We’ve also made some plans for field experiments trying to measure seismic and acoustic emission events from rocks fracturing here in the mountains of CA and eventually down in Antarctica. Once we have a better understanding of how to interpret the signals and relate them to rock breakdown we can propose to send a seismic network to an asteroid surface. That will be down the road, but it’ll happen someday and could mean a Shake in space!

IN CONCLUSION

So in the end, building PARSLEE was an incredibly challenging experience. Even two smart people with mostly complete instructions had to learn a lot to accomplish it. We wasted a lot of time doing things wrong, learning how to fix things, learning how to communicate better, arguing with each other, and generally being confused about robots. It was a really fun and a great learning experience, though at times a very stressful and frustrating project. But we did it! And you can too, if you want! It just takes some tools, elbow grease, and patience.

What would you do with your rover? Where would you take it? How would you modify it? Rove onward, friends- I hope you explore our world and others in whatever you do.

From all of us at Raspberry Shake we are extremely grateful to Dr. Jamie Molaro for picking up the story of her amazing mini-rover and it’s first big adventure to Burning Man. Good luck with your work and we will keep our fingers crossed for the possibility of sending a Shake up into space! – Thank you